Why you should be spending more on clothes

The environmental and social cost of fashion is high, but do we even care?

In a world of $10 T-shirts and next-day delivery, we expect clothing to be cheap, fast and replaceable. Fast fashion has trained us to buy impulsively, cycle through styles at a dizzying pace, and assume it’s normal to discard a piece of clothing after just a handful of wears.

But if we need to rethink anything in our era of overconsumption, it’s our disposable approach to clothing—and if we’re willing to invest in change.

When I say “spend more”, I’m not just talking about money. Spending more means investing more time, more energy, and sometimes, a bit more cash. It means reconsidering where our clothes come from, who makes them and what they’re made of.

A $10 T-shirt isn’t just a bargain; it’s a red flag. There is always a hidden cost behind that low price, and it’s often carried by someone, somewhere, who’s working in conditions far from fair, safe or sustainable.

Why pay more?

Somewhere along the line, the cost of clothing became divorced from its value. We’ve forgotten that every garment is the product of human effort: cutting, stitching, dyeing and finishing. This isn’t just factory labour; it’s a complex process often conducted at breakneck speeds to keep up with demand. When we see a shirt that costs less than a coffee and croissant, we need to ask ourselves: who paid for this, if not us?

Spending a little more on clothing can mean supporting brands that pay living wages, use safer dyes or implement measures to reduce waste. Yes, this may mean having fewer clothes in our wardrobes, but imo that’s a price worth paying.

The question of $$

I understand that this is a tricky subject. According to the 2025 McKinsey State of Fashion report, consumer interest in sustainable fashion remains inconsistent. Rising living costs are pushing everyone to adopt more cost-conscious behaviours. And even consumers who could afford to spend more are still buying from more affordable brands.

Sustainable fashion does come with a higher price tag. And it’s important to acknowledge and understand that a lot of people don’t see the immediate value in paying more. Why spend $50 on an ethically made shirt when a $10 alternative looks just as good in the short term?

Additionally, many consumers now prefer to spend money on experiences like dining out or travel, deprioritising discretionary spending on fashion altogether. When they do buy clothes, they opt for affordable options to leave more room in their budgets for other priorities.

I am also struggling in this cost of living crisis. (Butter is now $6 a block!?!) However, now is the perfect time to challenge how we think about value and what we’re spending on. Because if we’re not carrying the cost, who is? If we deprioritise the clothing we choose to buy, who will prioritise the people and planet responsible for creating our clothes?

The environmental and social cost

I genuinely feel like screaming thinking about the myriad of ways that the fashion industry is exploiting people and the planet.

Environmental cost

Clothing production is one of the world’s biggest contributors to pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. The statistics are staggering. A single polyester top has the same carbon footprint as driving 140 kilometres. Textile production is responsible for 20% of global clean water pollution. And intensive cotton production is causing an entire sea to disappear!* Every stage of clothing production has an environmental impact—whether through CO₂ emissions, water consumption or textile waste in landfills.

*The Aral Sea, formerly one of the four largest lakes in the world, has almost entirely dried up, largely due to intensive industrial cotton farming in Central Asia.

And it doesn’t stop there! Once clothes are out of the store and into our wardrobes we have to reckon with the millions of microplastics being shed from polyester clothes every time we wash them. Just one load of laundry can discharge 700,000 microplastic fibres that can end up in the food chain.

A 2020 study of Auckland’s beaches found that 88% of microplastic pollution on shorelines was attributable to clothing.1 On top of causing devastating impacts on local ecosystems, microplastics are also causing serious harm to our health.

“We can’t seem to stop spending, and we can’t seem to stop wanting to buy at cheaper and cheaper prices (which knocks on to the bottom line of those at the bottom). We consume and we consume and we consume, while not giving much thought to the lifespan of our clothes, or other people on our planet, or our planet itself.”

— Aja Barber, ‘Consumed - The Need for Collective Change: Colonialism, Climate Change and Consumerism’

Fashion’s hidden environmental toll might be conveniently out of sight, but it’s everywhere: in landfills, in contaminated waterways and in the microplastics that are now showing up in our fish and drinking water.

Social cost

The human cost of fashion is also impossible to ignore. In 2013, the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh killed over 1,100 garment workers and injured thousands more after workers were forced to return to an unsafe building under threat of losing their jobs.

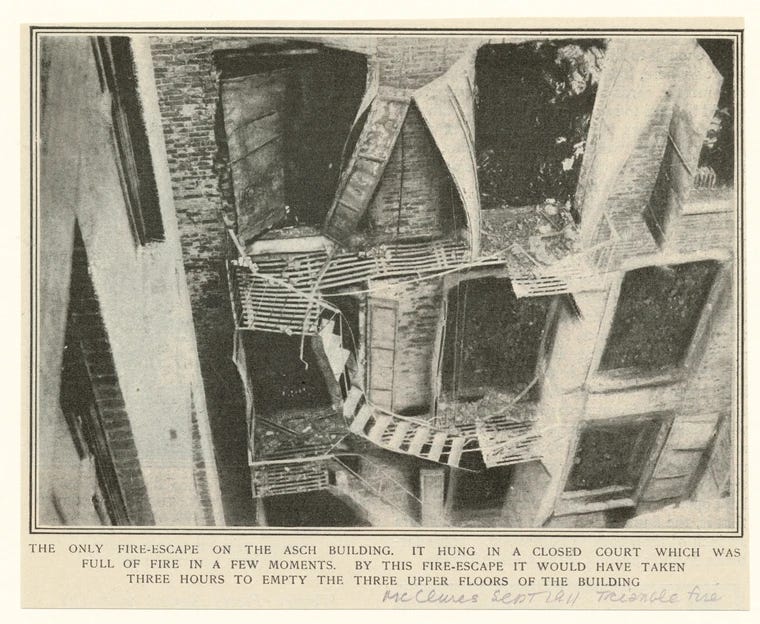

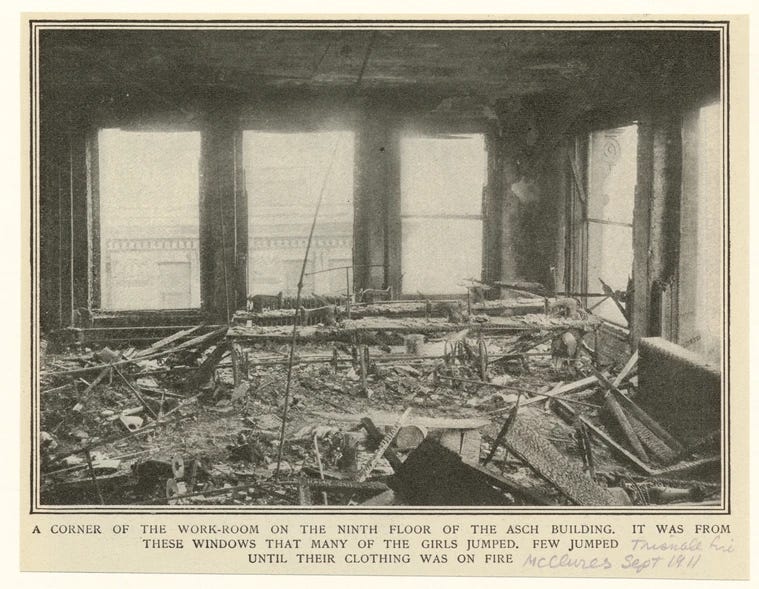

The Rana Plaza disaster shares similarities with the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. In 1911, 146 garment workers were killed in New York after a fire broke out in the garment factory. The factory was known to be incredibly hazardous, but bosses ignored the risks and locked the emergency exits to prevent workers from using the exit doors to take unauthorised breaks or steal from the factory floor.

When the fire started, the workers (who were mostly immigrant women in their teens and 20s) were stuck inside the multi-storied building. Those on the upper floors were forced to jump out of the windows to safety. However, most died from jumping or were killed in the fire.

Not much has changed between the fashion industry of the 1900s and how fast fashion operates today. Back in 1911, the women at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory were sewing cheap and accessible ready-to-wear clothing—just like the garments filling online shopping carts now. But that affordability came at a cost: low wages and exploitative working conditions. As consumer demand for these clothes grew, factory owners looked for ways to cut costs, often at the expense of worker safety.

The parallels between the Triangle Factory fire and the Rana Plaza disaster can’t be ignored.

These tragedies, and other exploitative practices ranging from sexual harassment to modern slavery, reveal the harsh reality stitched into the seams of our clothes.

But the biggest problem for most garment workers is the systemic issue of low wages.

Just like in Aotearoa, Australia and America – the cost of living is going up in key manufacturing countries like Bangladesh, Cambodia, Pakistan and Turkey. However, 89% of the largest global fashion companies (think Boohoo, Amazon, SKIMS) aren’t committed to paying the workers in their supply chain a living wage.2 This means that those workers can’t afford to live on the wages they receive. And “fears persist among governments and factory owners that higher wages could drive fashion companies to lower-wage countries” creating systemic incentives within countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan and Turkey to keep wages low.

Behind the cheap price tags is a system that profits off vulnerable workers—a reality we can’t afford to look away from.

As consumers, we can either perpetuate this cycle or try to be better.

How you can be part of the solution

Imagine if, instead of viewing our clothes as disposable, we approach our wardrobes with intentionality. Imagine seeing your clothes as an investment in yourself, the people who make them and the planet we all share.

We all have the power to redefine what "more" means in the context of our wardrobes. This is not a call to action to bankrupt yourself in the name of sustainability. But to spend more time thinking about your clothes, shopping intentionally, buying second-hand, renting event-wear and mending your clothes so they stay with you for years.

But sometimes we do need to spend more money. Well-crafted clothes made from long-lasting materials and created by well-paid workers will cost more! But how I see it is that those quality pieces are going to last so much longer in my wardrobe than a cheaper, lower-quality alternative.

With that in mind, I present to you my cost-per-wear formula! I use this to understand if what I’m spending my money on is worth it — or if I should rethink that purchase.

9 practical tips to becoming a more conscious consumer

If you’re ready to rethink your wardrobe and shop more intentionally, here are some practical ways to get started:

Buy Less, Choose Well

Focus on quality over quantity. Look for pieces you genuinely love and that will stand the test of time. Ask yourself how many times you’ll wear those clothes. What’s the cost-per-wear? Are you comfortable with your answer?Do Your Research

Familiarise yourself with brands that prioritise sustainability, fair labour practices, and transparency. Good On You is one resource to help you identify ethical brands. Check a brand’s “About” page or sustainability reports to see if their values align with yours.Invest in Timeless Pieces

Build your wardrobe around versatile staples that won’t go out of style—think classic cuts, neutral colours, and durable fabrics. These items are often worth the extra cost because they last longer and pair well with other pieces.Embrace Second-hand and Vintage

Op-shops, vintage stores, and online platforms like Designer Wardrobe, Vinted or Depop are great places to find unique, affordable, and eco-friendly pieces. Shopping second-hand reduces waste and extends the life of garments.Repair, Don’t Replace

Learn basic mending skills like sewing on a button or patching a hole. If DIY isn’t for you, find a local tailor or alterations service.Pay Attention to Fabrics

Look for natural, biodegradable fibres like cotton, wool, linen, and hemp. Avoid fabrics like virgin polyester and nylon, which are derived from fossil fuels and shed microplastics. Of course, this tip comes with caveats. Some technical garments like raincoats need synthetic fabric, and not all natural fabrics are the most sustainable option. But choosing natural over synthetic fabrics is a good rule of thumb for most clothing.Support Local!

Buying from local designers or smaller brands often means higher-quality items and more accountability in their production processes. Plus, you’re directly supporting someone in your community!Pause Before You Purchase

Impulse buys are often the result of micro-trends or emotional shopping. Give yourself a 24-hour window to decide if you really need or want something. Save the clothes you want in Carted, a notes app wishlist or in Notion and close! those! tabs!!!Take Care of What You Own

Washing clothes less frequently, using cold water and air-drying can significantly extend their lifespan. Proper care also reduces the environmental impact of your wardrobe over time.

Being a conscious consumer will help you curate a wardrobe you’ll cherish—and result in you contributing to a more sustainable and ethical fashion ecosystem.

James H. Bridson and others “Microplastic contamination in Auckland (New Zealand) beach sediments” (2019) 151 Marine Pollution Bulletin 110867.

Baptist World Aid produce the Ethical Fashion Report. The 2024 report is their 10th annual report. 120 fashion companies were assessed representing over 450 brands.

I have so many times I sew something and people think it is a complement when they say "I would buy that!" or "You could sell that." One time I added up the costs for a pair of pants with a lot of Canadian smocking and hand embroidery I made and posted this: "ripstop cotton fabric: $14.97 + $7 shipping (I found a great sale!), thread $19.50 (should have a lot left for future projects), $6 Perle cotton floss, $.74 zipper, $.15 elastic and buttons. So about $50 worth of materials. I have already spent 10s of hours designing, making a mock up and putting together just this small part. I am guessing over 100 hours by the time they are done. If we “fight for $15” that would be an additional $1500 in labor. This does not include the cost of my sewing machine, serger, cutting tools, marking tools, pins, needles… All for a pair of pants that will serve the same function as something I could have picked up in the thrift store for less than $5."

Then I read somewhere that the average piece of clothing gets worn less than 10 times. My $1450 pants are going to get worn until they are thread bare, at which point they will probably be patched back together adding even more detailing. When you realize the effort that went into something you value it a whole lot more.

I SEW heartily agree and have been preaching this to whoever will listen for years. My sewing students here at my Sunroom Sewing Studio in Jackson, TN - USA - often remark that they had NO idea how many steps it takes to make clothing! Preach it, girl - preach it! My favorite type of sewing - for inexpensive 'fabric' are thrift stores. I sell my creations if you're interested: https://www.londas-sewing.com/londas-originals I also teach Upcycle Sewing - will be doing so to many US women online on May 1 - part of American Sewing Guild and then again at a regional hands-on conference in Chattanooga, TN in late Sept. I love not only the sustainability of upcycle sewing, but also the creative challenge of it!